My Love/Hate Relationship with Wes Anderson

by M.A. Fedeli

Wes Anderson's films are entertaining. Wes Anderson's films are beautiful. Wes Anderson's films are often hilarious and filled with memorable people, animals, and sets. But for many of the same reasons that make me admire him, I also wind up unsatisfied. Where he loses me is first in the emotions department, and second, in overall fulfillment. The films are truly never the sum of their parts, but the parts are incredible indeed. While tackling dramatic themes, his films adopt a tone where the more depressed his characters get, the more amusing they get. And if that's his point, which it very well may be, well then, what's the point? If this dynamic is what Anderson does, then isn't he just Judd Apatow with a great eye, brilliant camera work, and catchy tunes? On second thought, maybe that's not so bad. Maybe that's why I still look forward to his films.

True, it is hard to turn away from a Wes Anderson picture; there is so much going on for the eye to delight in, and there are few wasted visual moments. But the characters have perhaps too much character to be taken seriously. For all their lofty goals, Anderson films feel like a finely crafted version of Caddyshack, complete with Bill Murray, wacky families, and the super rich. The characters are by no means caricatures, but they are cartoons, so overloaded with quirks and distinctive traits that they don't feel real on many relatable levels. They are a bit too odd and contrived to get too invested in. Sure, his films have legions of die hard fans who wish their world more closely resembled the world Anderson admirably puts on celluloid, but that says more about them than anything else.

much character to be taken seriously. For all their lofty goals, Anderson films feel like a finely crafted version of Caddyshack, complete with Bill Murray, wacky families, and the super rich. The characters are by no means caricatures, but they are cartoons, so overloaded with quirks and distinctive traits that they don't feel real on many relatable levels. They are a bit too odd and contrived to get too invested in. Sure, his films have legions of die hard fans who wish their world more closely resembled the world Anderson admirably puts on celluloid, but that says more about them than anything else.

Not every character in Anderson's recent films is a cartoon. When a Gene Hackman or Seymour Cassell (both born and bread in early cinema 70's realism) grace the screen, you can see the red blood pulsing through their veins, and it's in those moments Anderson's genius shines. In the director's most recent effort, The Darjeeling Limited, it's Angelika Houston's rational earth mother who pumps out the same verite that Hackman did. Her human, grounded performance only serves to highlight how irrational and absurd her sons are as fictional characters. She exposes them all as clowns, mopishly playing everything for gags. And these are the main characters we are supposed to have a vested interest in? Unless we aren't, in which case, well, what's the point?

I am being hard on poor ol' Wes, who shines compared to most modern filmmakers. So lets just say that this essay is where I pick on his weaknesses as compared to the Renoirs, Welles', and Kubricks. I do understand and find redeeming value in playing sadness for laughs, like Ron Burgundy in a phone booth. The problem for Anderson is that the only real reason to revisit his films is for the visuals and laughs (and perhaps the melancholy, if that's the mood you're in), as the films themselves are psychologically light. That said, he is a fascinating visual story teller in that he keeps you watching, even if you don't really care what happens at the end. Anderson does tracking shots, pans and slow motion in interesting and arresting ways. In Darjeeling, watching the brothers chase a train in super slow motion is great, encompassing more consequential drama in those moments than in the rest of the film. Watching them walk in slo-mo past a dead boy's elaborate funeral preparations, however, only serves to make sure you don't miss how damn beautiful Anderson's set-ups, costumes and backdrops are. But with the beauty Anderson puts on display, even that's okay.

Fun and creative as they are, I'd like to see Anderson break out of his familial angst plot-lines and experiment in a world where characters cannot always fall-back on decades long history between one another in order to relate; where the world is not only the hopelessly maudlin world of the privileged and their servants. Though I can't get them out of my head, I'd like to see him rely less on quirky music choices. While catchy, the tinkly, precious songs Anderson chooses ultimately make the film a uni-tone flat line with only one prevailing mood all the way through: worn-out wistful. Compare that with the musical choices of Paul Thomas Anderson, who has brilliantly used 4 completely different sounding soundtracks for 4 completely different feeling films.

Wes Anderson should actually be thankful for a film like Garden State, which shows us how much worse it can get in this land of melancholy and woeful quirk. Anderson's characters may be cartoons, but at least his films believe in them and respect their problems. Despite my own aggravation, if harsh realism is tossed out the window I suppose it is more admirable to play desperation for laughs than for noxious melodrama. Garden State exploits it's characters quirks simply to drain as much silly melodramatic dole from them as possible; talk about not having a reason to care what happens in the end.

So, as I tried to explain in the beginning, I have equal parts admiration and frustration with Anderson's work. Unlike M. Night Shyamalan, Anderson's films are still events. But unlike P.T. Anderson's, you can wait a few weeks.

Read more!

Monday, March 24, 2008

The Darjeeling is Limited

Posted by

Mark A. Fedeli

at

1:29 PM

7

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, January 10, 2008

The Wire

Wasting From the Inside

By M.A. Fedeli

"It's called the American dream because you have to be asleep to believe it." -George Carlin

The fifth and final season of The Wire on HBO has begun. And not since The Sopranos has so much print space been dedicated to hailing a television show as the best on TV. Whatever The Wire is, it is certainly the most thoughtful and intelligent drama on television. Beyond that, however, it is the most patiently well-crafted storytelling the tube has seen in a while. It is the closest thing to reading a classic epic novel that you will find on TV. The plotting is restrained, the characters are not indulgent, and the storylines are just as faithful to reality as they are to entertainment; a massive achievement in this day and age and an aspect that may go a long way to explaining why The Wire (along with its Baltimore location) does not have huge ratings by any standard. What The Sopranos says about the soul; what Six Feet Under says about coping; what Sex in the City says about, well, sex in the city, The Wire says about the almost complete erosion of the American Dream. The Dream, sometimes defined as the ability of anyone to achieve prosperity with hard-work, has been supplanted over the years with the thought that everyone in this country is owed prosperity, hard-worker or not. It is in this spirit that we find The Wire: examining the American sense of entitlement that contributes to much violence, corruption, and crime in this country; examining the grinding wheels that have ground to a halt -- the contingency plan supposed to protect us from the worst we have to offer. The Wire does not stop there with it's blame, however. Unlike most "cop" shows or "lawyer" shows or "crime" shows or "political" shows, The Wire deftly hands out blame to all aspects of our culture, our institutions, and ourselves.

What The Sopranos says about the soul; what Six Feet Under says about coping; what Sex in the City says about, well, sex in the city, The Wire says about the almost complete erosion of the American Dream. The Dream, sometimes defined as the ability of anyone to achieve prosperity with hard-work, has been supplanted over the years with the thought that everyone in this country is owed prosperity, hard-worker or not. It is in this spirit that we find The Wire: examining the American sense of entitlement that contributes to much violence, corruption, and crime in this country; examining the grinding wheels that have ground to a halt -- the contingency plan supposed to protect us from the worst we have to offer. The Wire does not stop there with it's blame, however. Unlike most "cop" shows or "lawyer" shows or "crime" shows or "political" shows, The Wire deftly hands out blame to all aspects of our culture, our institutions, and ourselves.

The show prides itself on the crisp thematic divisions of its seasons. Each season even comes with a new credit sequence and a newly recorded version of the theme song. The new credit sequences reflect the pertaining season as a whole, mirroring the subject matter and trajectory and offering small clues to the season's progression that don't become apparent until you experience them in the episodes. The Wire's police and thieves saga has 5 chapters: Among other things, Season 1 deals with detectives and drug dealers; Season 2 adds on unions, dock workers, and international crime; Season 3's additions include neighborhood and institutional breakdown, city government and political corruption; Season 4 garnered unmatched reviews with its inclusion of the educational system, inner-city children, and family.

From all signs, Season 5 will be dealing with all of the same and bringing the media into the fray, specifically city newspapers. More specifically, The Baltimore Sun, where show creator David Simon worked for years until he was fed up with the ineffectualness of journalism. He explains, "One of the sad things about contemporary journalism is that it actually matters very little. The world now is almost inured to the power of journalism. The best journalism would manage to outrage people. And people are less and less inclined to outrage."  From the looks of the first couple episodes, weariness and defeat seem to also ready to play a big role. Simon explains, "The Wire's basically about the end of an empire. It's about, This is as much of America as we've paid for. No more, no less. We didn't pay for a New Orleans that's protected from floods the way, say, the Netherlands is. The police department gets what it pays for, the city government gets what it pays for, the school system gets what it pays for. And in the last season, the people who are supposed to be holding the entire thing to some form of public standard, they get what they pay for."

From the looks of the first couple episodes, weariness and defeat seem to also ready to play a big role. Simon explains, "The Wire's basically about the end of an empire. It's about, This is as much of America as we've paid for. No more, no less. We didn't pay for a New Orleans that's protected from floods the way, say, the Netherlands is. The police department gets what it pays for, the city government gets what it pays for, the school system gets what it pays for. And in the last season, the people who are supposed to be holding the entire thing to some form of public standard, they get what they pay for."

You can't constantly lower taxes and expect to get the same level of public services. You can't fight a trillion dollar war and expect other aspects of the government not to suffer. Politicians are afraid to ask for our sacrifice because they are afraid of us! How many of us would vote for a candidate if they told us taxes would have to be raised 5 to 10 percent for programs that may never directly affect us? Maybe years ago a majority would be open to such an idea, as we sacrificed greatly during WWII, but most in this country have been programed by the panderers since to believe that taxes are already to high; that government is already too big. And what of the media, the guardians of the public mind, the ones who are supposed to keep balance? They are marginalized by capitalism, technology, and the magic of "access": If you roast your subject, your subject will no longer grant you access, your stories will lack exclusivity, you wont be as successful, you make less money, and etc. and etc. and etc.

The system has worked itself into a corner. After the 60's, politicians learned exactly how far they could push people and exactly how far people would be willing to push back: not very far. No amount of realistic public demonstration will sway much in the halls of power. Even if you were to amass an imposing sized group (say, the amount of people who vote for American Idol) the same amount of people would automatically stand against you. Why? Just because. This is  the absolute backlash of playing red state and blue state against each other; it's re-fighting the Civil War in the land of non-thinking while the generals hide behind desks. The American system of government has been at work for less than 250 years. As time goes by, those at the helm have learned how to better grease the rails for their own devises and how to spin it all so there is little repercussion. Each day that goes by is one more day on the job where they learn how to perfect their routine; where they see how far the thing bends before it breaks; how much shit we'll eat. The standards and expectations have crashed through the floor; it's every man for himself.

the absolute backlash of playing red state and blue state against each other; it's re-fighting the Civil War in the land of non-thinking while the generals hide behind desks. The American system of government has been at work for less than 250 years. As time goes by, those at the helm have learned how to better grease the rails for their own devises and how to spin it all so there is little repercussion. Each day that goes by is one more day on the job where they learn how to perfect their routine; where they see how far the thing bends before it breaks; how much shit we'll eat. The standards and expectations have crashed through the floor; it's every man for himself.

Only one example is really needed: just look at what our President has been able to get away with, look at how far he's been able to push his own, unconstitutional agenda. Brazenly he has done things that no one thought could be done within our system of checks and balances. And look, he is still President and still defended. The best thing George W. Bush has done for this country is show us just how broken the machine really is. We may actually, hopefully, wind up thanking him for opening our eyes to that in the long run. But probably not.

The castle is collapsing and The Wire is giving us a view from the inside. It's credibility is ensured because it passes out the blame equally to all who deserve it. Simon's view seems to be that we all deserve it. And of course we do, and we all know it. Don't we?

Posted by

Mark A. Fedeli

at

4:29 PM

5

comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, January 8, 2008

Lost in the Woods

It's Critical, but is it Art?

By M.A. Fedeli

"In many ways, the work of a critic is easy. We risk very little yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face, is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is more meaningful than our criticism designating it so."

Roger Ebert? Richard Schickel? Pauline Kael? Andre Bazin? None of the above. This quote is from Anton Ego, the harsh and unforgiving food critic of Disney's Ratatouille. This, combined with the critical maelstroms that have risen up around films such as There Will Be Blood and No Country For Old Men got me to thinking, what is criticism worth? Is it a worthy addition to the artistic landscape; a valuable service to society? Or, is it: "those who can't do, criticize"? Thankfully, Mr. Ego offers one final thought in his self-assessment:

None of the above. This quote is from Anton Ego, the harsh and unforgiving food critic of Disney's Ratatouille. This, combined with the critical maelstroms that have risen up around films such as There Will Be Blood and No Country For Old Men got me to thinking, what is criticism worth? Is it a worthy addition to the artistic landscape; a valuable service to society? Or, is it: "those who can't do, criticize"? Thankfully, Mr. Ego offers one final thought in his self-assessment:

"But there are times when a critic truly risks something, and that is in the discovery and defense of the new. The world is often unkind to new talent, new creations; the new needs friends."

The most modern and relevant version of this conundrum is perhaps the critical triumph of smaller "indie" films over mega-hit blockbusters. Do critics shine a light on smaller, more deserving films with little promotional budget, or, are they simply full of themselves and spite for anything big-budget, crowd-pleasing, and Hollywood? For an attempted explanation, I refer to this Question & Answer exchange between Roger Ebert and one of his readers:

Q. I almost skipped going to see the newest "National Treasure" movie after reading numerous poor reviews. But, as always, I underestimated the ability of our national movie critics to understand the likes and dislikes of our true national critics -- the movie-going public! My family had a great time watching "National Treasure: Book of Secrets." True, it was far-fetched, but it was two hours of escape from the real world. I guess, Mr. Ebert, you gave Mr. Depp's new movie, "Sweeney Todd," four stars since it is more believable and fun entertainment for the holidays. Merry Christmas, Mr. Scrooge!

Scott King, Chapel Hill, N.C.

A. I don't think you underestimated us at all. Overestimated is more like it. However, the critic's job is not to reflect public opinion. If that's all he does, the public is the ventriloquist and the critic is the dummy. I have gone back and carefully read both of those reviews, and I think you must concede they are both accurate descriptions of the movies. It is not the critic's job to reflect public opinion. This sounds pretty standard and acceptable in a vacuum. However, when applied to the criticism mainstream art like movies, music, and tv, it sometimes get accused by the general population of being snobbish and out-of-touch. In comparison, Scott King from Chapel Hill probably isn't concerned with the critical opinions of high art in The Metropolitan Museum. Yet, everyone in your office has a thesis on The Lord of the Rings. In the land of Mcdonalds and Michael Bay has the film critic been rendered obsolete?

It is not the critic's job to reflect public opinion. This sounds pretty standard and acceptable in a vacuum. However, when applied to the criticism mainstream art like movies, music, and tv, it sometimes get accused by the general population of being snobbish and out-of-touch. In comparison, Scott King from Chapel Hill probably isn't concerned with the critical opinions of high art in The Metropolitan Museum. Yet, everyone in your office has a thesis on The Lord of the Rings. In the land of Mcdonalds and Michael Bay has the film critic been rendered obsolete?

Well, follow the money. Hollywood makes more in a week than all the major U.S. museums combined, even if they charged full fare! Your average person, if seeking only base entertainment and escapism does not usually go to The Met; but they do go to the movies. A lot. Or a lot more often, at least. And Hollywood excels at cashing in on the most basic desires of our psyches and guts by pumping out visceral adrenaline like Transformers and confused schlock like From Justin to Kelly (a film that pretty much defies all reason and sanity). There is nothing in The Met that is anymore magnificent or inspired than history's finest cinema; both are full of wonderful artistic and humanistic achievements. The Met, however, is not forced by its owners to forgo art almost all together and have promotional installations for NASCAR or Barney.

Given the average audiences tastes, it is almost a testament to a film's ambition and intelligence if it is not a bankable success. In their original runs, neither Goodfellas nor Schindler's List grossed over $100 million domestic. That's the 4-day opening weekend goal now for most blockbusters! So, in the zeitgeist wilderness in which we live, the critic does provide the extremely necessary function of separating the flowers from the weeds. In the words of art critic Donald Kuspit, a critic's job "is to try to articulate the effects that a work of art induces in us, these very complicated subjective states." Famed Aesthetic and critic Walter Pater believes good critics can best answer the following for the rest of us: "What is this song or picture, this engaging personality presented in life or in a book, to me? What effect does it really produce on me? Does it give me pleasure? and if so, what sort or degree of pleasure? How is my nature modified by its presence, and under its influence?"

Famed Aesthetic and critic Walter Pater believes good critics can best answer the following for the rest of us: "What is this song or picture, this engaging personality presented in life or in a book, to me? What effect does it really produce on me? Does it give me pleasure? and if so, what sort or degree of pleasure? How is my nature modified by its presence, and under its influence?"

He also believes, "Beauty, like all other qualities presented to human experience, is relative; and the definition of it becomes unmeaning and useless in proportion to its abstractness. To define beauty, not in the most abstract but in the most concrete terms possible, to find not its universal formula, but the formula which expresses most adequately this or that special manifestation of it, is the aim of the true student of aesthetics."

It may be true that within each film critic lies a defeated filmmaker, but that does not necessarily mean that criticism is any less valuable than the art itself. Both perform an integral act; both offer a perspective on life: films as a reflection of existence; criticism as a reflection of what exists. I, for one, feel better now. So, to mark this special occasion, I present for you the snarky diatribe that is my first ever film critique: an overlong, overwrought, overzealous piece of concentrated anger directed at M. Night Shyamalan's The Village...

http://getthebutter.blogspot.com/2008/01/shyamalans-folly-by-m.html

Posted by

Mark A. Fedeli

at

7:08 PM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

The Village from The Woods

Shyamalan's Folly; My First Review

by M.A. Fedeli

Author's note: This review was written in 2004.

There are a few obvious rules that aid making a good film, but there are a gaggle of rules for making a bad film. That said, it seems M. Night Shyamalan has followed those geese closely in making his period/love story/murder mystery/monster movie/psycho-political thriller/pro-communist fable, The Village. The fact that Night did not appear to have much of a clue about exactly what kind of movie he was trying to make is The Village’s greatest weakness. The film changes gears more than a ten-speed as it unfolds. This is fine at first, as it moves from a slow-paced period (or should I say, costume) mystery into a taut and engaging thriller, housing some of the most visually imaginative, minimalist monsters ever brought to film. But as it progresses into its third and fourth acts the film falls apart and spirals into a tangle of absurdity.

Click the link below to read the rest of this review.

The village in The Village is inhabited by those who are elders and those who are not. The time period is the 1890’s, which we learn because of a tombstone during the opening scene: a funeral for a child. The impetus for the early action in the film is this funeral and Lucius’ (Jaquin Phoenix) frustrated urge to venture outside the village and into the dreaded “towns” to find new medicines and cures for the village residents. “The Towns” are awfully violent and decadent places though, so Lucius is quickly forbidden and discouraged by the group of elders (G8 anyone?). You see, our movie village is frozen in time (though time does not usually seem to heed to these demands) and operates with Amish sensibilities; modern medicine and the advancements of the outside world represented by “the towns” have no place.

Oh, apparently the woods surrounding the village are inhabited by horrible, blood thirsty monsters, or as they are affectionately called, “those we don’t speak of.” They must be “those we’ve never seen” as well because there is no explanation in the film for how “those who are not elders” contracted their terrible fears since we seem to have dropped in on the only time any of this has ever become an issue. There seems to be a well-established pattern of behavior for events that have never happened before. However, in the film’s first political statement, it does seem as though the elders have spun the yarn about the ferocity of the monsters well enough to effectively freak out everyone in the village. So I guess that’s good enough. Folks, this is the film, and it’s a darn good premise, I’ll admit that. Perfect territory for Shyamalan, or so we thought.

The tone of the first two acts is slow moving, re-creating for the audience the pace of life in this quiet village. Whether or not the acting is solid or the dialogue is truthful is irrelevant. We know we are at a monster movie but for the first time since Jaws we have no idea what to expect and when to expect it. Instead of being distracted by naked teens, toilet humor, or standard psychological thriller fare, we are lulled to sleep, left uniquely unprepared for the shocks and thrills to come. This is Shyamalan’s Bergman impression, it works well and it is a very good idea for a suspense film. This is the kind of filmmaking I love; when the director lets you experience the movie, not just be entertained by it. It hearkens back to the silent era when you could not rely on words. That seems almost paradoxical, being as a lack of words would naturally seem to cause a need for and a rise in action, but not really. The ensuing action must be slower and more telling, as it takes more time to describe and display a dramatic scene in silence as opposed to just quickly stating and explaining it.

The film starts to fall apart before we even realize it. This unwinding is embodied by Adrien Brody’s very visible character, Noah Percy. This is undoubtedly the most uninspired mentally handicapped performance since Harrison Ford in Regarding Henry. (How do you determine a thing like that? Brody was not nominated for an Oscar, so you know he must have screwed up bad. How hard is it to land an Oscar nomination for playing a handicapped character? They give out nominations for that kind of role when you get off the plane at LAX. Ford should be more embarrassed though, considering his film came in the Golden Years of handicapped nominations (DeNiro, Pacino, Hoffman, Day-Lewis, DiCaprio, etc.). That is, unless you subscribe to the theory that Brody had no competition, so had it much easier. You could argue for both.) The problem is, Shyamalan and Brody have no idea exactly what kind of handicap Noah is afflicted with, and it doesn’t seem like they care to know. For the ridiculous second-half of this story to work, he has to be extremely stupid and extremely cunning, extremely sweet and extremely violent all at the same time (and not in a Rainman kind of way). Brody’s character grows in importance as the story progresses and ultimately is the film’s most important character, as well as it’s most contrived and confusing.

I am going to skip over the rest of the details of the film, they are all rendered insignificant by the soon-to-come runaway plot. The last highlight of the film is the end of the second act and the first sightings of the monsters. It is Hitchcockian/Langian in its execution, and done with tact and precision to rival the best moments of horror-epic The Shining. Along with fantastically imaginative costumes, there is a perfect balance of what is shown, how much is shown, and how often it is shown. We are on our toes, eager and curious and ready for more, exactly where Shyamalan should want his audience to be.

Then comes Act 3, and Shyamalan’s insulting need to expand plots for the sole purpose of explaining it all with some shocker of total closure in the end. This is formulaic and predictable filmmaking at its worst because Shyamalan is clearly a talented man, capable of going above and beyond your typical genre pic. Or maybe he isn’t. Maybe this film is his attempt to go above and beyond genre only to have his natural urges turn it all into a muddy mess. The Village would have been far better off as a genre pic, where everything is as it seems; monsters are monsters, they scare you and they eat your young and they disappear and then you have to respond somehow, hopefully in some new and interesting way. End of story.

It’s also the end of this movie. In his vain attempt to do something completely different, Shyamalan created a superfluous plotline, and wound up doing something completely absurd instead. He blows his load, which he’s worked so hard to store up, right after we see the monsters. Everything that is done by the characters from here on out is done for love, which would be excusable except for it’s not what we signed up for.

A love triangle leads to Noah stabbing Lucius. The maiden in question is Ivy, a blind lass who could play goalie for the Philadelphia Flyers if it suited the ridiculous plot. For love, she now wishes to visit “the towns” to get medicine for the dying Lucius, taking up his old cause except for her own completely selfish reasons (bring back enough for everyone, babe!). With Noah (who is amazingly aware of his actions while at the same time amazingly unaware of them) locked in the room where bad people go, Ivy petitions to the elders to let her trek through the woods. By the way, I have heard that The Woods was considered as an original title for the film. You get the feeling that the original idea for this film, before it was pilfered by Shyamalan’s crutch, had more to do with the (actual) monsters in "the woods" and less with these boring, (sometimes) contraction-free villagers. At least, it should have.

Anyway, Ivy convinces her father, William Hurt’s Edward Walker, the lead elder, to let her go to the towns. Just imagine a modern teenager trying to convince her father to let her go out on a date with Johnny, the kid from the other side of the tracks who lives in the house with no front lawn, just dirt and rocks. Anyway, this is the first loud, disappointing thud of the film! Eddie kind of lets us all in on the secret that the monsters are not real; they are just the elders in awesome costumes. Great, can we just leave the theater now? It’s at this point, with much running time to go, I realized that the film is going to be all about contrivance and not substance. Here’s why the audience should be incensed that the monsters are farce: the monster costumes they created for this film were ingenious. We deserve another film with REAL monsters that look like these. I found myself wishing we could be allowed to believe the monsters were still real because fake monsters is the worst plot resolution since, well, the one that happens in the end of this film that has us thinking that in comparison, the fake monsters bit wasn’t all that bad. I really wish any of this still mattered though, because by this point in the film the entire production only really exists to trick the audience as much as possible. This is patronizing filmmaking and unfortunately, it’s a good enough reason to make a film these days.

(I don’t have to point out how impossible it would be for Ivy to do what she does in the woods, but since I already have; the blind girl is sent on her way though the deadly woods to the equally harsh towns by her “loving” father where she does a bunch of stuff a blind person probably cannot do alone, unless she is a bat. Oh, and it only gets worse.)

The rest of this film is so obnoxiously bad that I barely feel like writing about it. Any intelligent audience will realize that many of the earlier scenes in the picture were corrupted so we could be more easily fooled. For example, conversations between elders (the supposed “all-knowing”) are intentionally made vague and misleading so we think they are talking about something else entirely. This is only done to expand the shock value of the film’s twists. No recent films have had more clear and effective twist endings than The Usual Suspects and Seven, yet rarely are any scenes in those films played unrealistic or the dialogue made vague in order to mislead the audience and hide the ending, unless the characters are choosing to mislead each other, which is different and acceptable. There’s a whole other level of clever in those two films, and it’s a level that mainstream Hollywood has been trying to emulate, unsuccessfully, ever since. As for Shyamalan, he puts way too much stock into his surprise endings and it backfires horribly in The Village.

Back to the story, for someone who probably needs constant supervision, Noah seems to wonder off unnoticed an awful lot. We are supposed to believe he skinned the animals that caused the latest uproar. Or did he? It doesn’t matter anyway. Apparently he found one of the costumes they hid under the floorboards beneath their version of a jail cell, of all places. Oh, please. Why on earth would you hide it there, where all the last people you’d want to find it hang out? The answer is you wouldn’t unless you needed your crazy character to find them so you could extend your absurdities. So what were the animal skins for if he found a costume? Don’t ask. I still don’t know if the skinned animals were intentionally left up to interpretation and the audience’s imagination, put in solely for confusion, or if Night didn’t feel like tacking another ten minutes of plot-hole-filler on to the film with a concocted story to explain it (I really don't mind some plot holes, I don't want to sit in the theater for 6 hours. They just have to be ones you can still drive over without tearing out your whole transmission).

Anyway (again), Noah manages to break out of his jail, unnoticed, and while wearing the costume, manages to find and attack Ivy in the woods (or he’s playing with her, who knows what hell he’s doing), until she kills him, never sure if he was real or her imagination because she’s blind, remember? I almost didn’t. When your plot is absolutely preposterous, the things you have to do to justify it are equally preposterous. This was the last moment of confusion in the film because for a few minutes we too didn’t know who was in the monster suit, if it actually was a real monster, or if it was her imagination. Wow, big surprise, it was Noah, he IS crazy after all! While we’re on that subject, how did the elders, who all seem to have kids, sneak so effectively in and out of the houses and village wearing these costumes? Where is the Clark Kent suspicion? You know, never in the same place at the same time. This movie falls apart under cross-examination, and for a filmmaker who tries so hard in all his films to explain the seemingly unexplainable, that is death.

Long story short, by the end we find out it’s not 1890, it’s present day, and that’s the big surprise, I guess. This ending is insulting. Why does it matter that it’s 2000 instead of 1900? As far as the characters are concerned it doesn’t matter at all (as tribute, I tried to use no contractions for this article but I am weaker than some of the acting in the film). The "towns" (cities) are still dirty, corrupt places, in 1890 and now. This is just shock for shock’s sake. This is an ending from a distracted filmmaker for an unsophisticated audience that is impressed with shiny things like big surprise endings, no matter what they are.

The entire second half of this film is not an exposition of characters and what happens to them, it is an amusement park ride for the audience. It is the biggest rule you can break; making a movie purely for the basest instincts of a dense audience. As enjoyable and suspenseful as Shyamalan’s films are, his obsession with shock endings explaining the already impossible is tired. Take The Sixth Sense, every scene with Bruce Willis and someone other than Haley Osmet has to be manipulated so WE don’t realize Willis is dead and not really interacting with anyone. Is that truthful and intelligent art, or is it just manipulative theater from clever-obsessed Hollywood? (Verbal Kint and Agent Kulluon don’t have that problem, they speak plain, realistically and bluntly, only trying to fool each other. Any attempt to trick the audience is achieved by smart, patient writing and an unflinching plot)

There are so many holes in The Village I don’t have the time or inclination to address them all, unless you have a fortnight to kill. They are not the kind of holes that are remotely clever, or that you take dramatic license with or suspend your belief/disbelief for (like Hannibal Lechter sneaking out of his maximum security holding pen with someone else’s face). They are the kind of holes that are created because the beginning of the film seemed to be written with a different ending in mind than the ultimate ending. When you love that beginning idea so much and don’t feel like changing it to adapt to your absurd ending, more holes than a Pottery Barn in Dresden is what you get. This is fiction, you have the ability to go back and do-over, to re-write and re-imagine, don’t be afraid! This may all seem very nit-picky, but the point is, the film is so lost and confused with itself that almost everything can be deconstructed. It’s like telling a lie to cover up a lie that covered up a previous lie. That feels like the process Shyamalan underwent for this film: he had an idea about a period movie with monsters in the woods and then lost control as he tried to expand the plot. In searching for his trademark gimmick he just kept building bad plot line onto bad plot line.

Noah’s character is a metaphor for this film: seems like it’s going to be one thing, but turns out to be something else completely, and then switches back and forth a few more times without rhyme or reason or rational until you just don’t care anymore. Like I said, this film lost me when it confirmed my worst pre-film fears and made the monsters fake. Isn’t that the entire film though? Wasn’t this film about a village dealing with monsters? It should have been because if it was it could have been one of the best suspense movies of modern times, it had all the perfect elements. Everyone, before going in to this film, had to think that one extremely possible, cheap, and disappointingly obvious plot twist would be for the monsters to be fakes. Shyamalan must have known this but decided to do it anyway, and thought throwing on a bunch of other unnecessary twists to distract and justify would mask the fact he had no other good ideas for where to go after the first 55 minutes. Bad decisions were made, and rarely is it so easy to point to such glaring things and know undoubtedly that they are the reasons a movie does not work.

People think this film is a political metaphor, a social statement, an interpretation of global events and paranoia. Unfortunately, it is all of those and none. Shyamalan is in over his head with all the statements he is apparently trying to make, because God knows, he definitely isn’t trying to finish telling a creative story. His attempts to be fresh and surprising all come off as tired, predictable and cliché. He cannot handle the multiple purposes, motives and plots running concurrently within this film. He is not Jean Renoir and this is not Rules of the Game. This film should have simply been about cool monsters terrorizing a village and the hopefully new and interesting ways the villagers go about solving the problem (or something even better that any of us could never think of, hence us not getting paid millions to write and direct big budget films!). Unfortunately though, subtlety and simplicity in film disappeared not long after Mr. Lucas decided to tell stories about good and evil in space. If Night could not come up with any resolutions that were as interesting as the monsters, he simply should have waited and made this later when he actually had a good idea and the ability to direct it. Oh, and it should have been called The Woods.

Posted by

Mark A. Fedeli

at

6:52 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, January 3, 2008

There Will Be Blood

There Won't Be Morals

by M.A. Fedeli

Oscar Wilde said, "Any element of morals or implied reference to a standard of good and evil in art is often a sign of a certain incompleteness of vision. All good work aims at a purely artistic effect." And so, after a viewing of P.T. Anderson's latest, There Will Be Blood (for my money the best film of 2007), this quote learned in my (not quite) halcyon college days was in mind. The film is refreshingly devoid of moral judgment. The characters are presented in all their conflicted glory, no apologies made by the film or its tone for their indiscretions, failings, and wrongdoings. But who does and what are wrongdoings anyway? Is it the ambitious oil man, with his paranoia and unapologetic capitalism, or, the manic evangelist, hiding his motives and schemes behind religion and its fables? There is good and evil in all of us, our experiences and situations help determine, then mete out which one will represent us at any given moment. If you are one who believes that there are no moral absolutes in human nature, then this may be the film for you. It is a story of ambition and the hurdles one must overcome, moral and otherwise, to achieve success. If the film has a lesson of its own, it is that lessons are irrelevant. We are all animals, some are just weaker than others.

The film is beautiful and well-crafted. P.T. Anderson continues to be a film buff's filmmaker, much like Kubrick was a filmmaker's filmmaker. PTA (as he will now be known) takes aspects of history's best directors and films and repackages them in wondrous ways that are satisfyingly unique and modern as much as they remind us of the real halcyon days of cinema. For anyone who loves 70's American cinema, Scorsese, Kubrick, Altman, Malick, Cassavetes, even back to Welles, Huston and Ford, Anderson is your man. And like Godard, he is not afraid to take chances that threaten to take you out of the world of the film. Anderson uses dialogue as art, both in its complex poetic beauty and in it's reflection of the awkward ways in which we sometimes speak it. Great confidence is needed to write dialogue that is unafraid of being not only challengingly poetic, but also clunkily realistic, and PTA exudes it in spades, unwary of having it jar the audience's accepted notions of "proper film dialogue." I admit to not liking any of PTA's earlier films the first time I saw them in theaters. I did not "get it" until a year or so after Punch-Drunk Love was released, when I gave all his films a second chance on DVD. He has since become my favorite, and I think most satisfying young American director. This will not be a long critique, it seems much ink has already been spilled about a film most people won't have the chance to see for at least a few more weeks. Also, I myself really wanted to see it again before I got too deep with a review, but I just couldn't wait any longer to write about it. It is a purely riveting picture and the always great Daniel Day-Lewis, as patiently dedicated oilman Daniel Plainview, is excellent beyond words. As the film unfolds, we have a front row seat for the events that occur to more and more disillusion and alienate an already detached man from the world, hacking away at what little faith he has left in humanity. The picture is almost a vehicle for Day-Lewis' grinding depiction of a man's slow descent into a self-imposed, isolated madness. Paul Dano, as the savvy evangelist Eli Sunday, admirably holds his own against the world's greatest working actor. The pitting of the fierce business man vs. the zealous religious man may seem obvious on the surface, but nevertheless, the dialogue and the actors make it deliciously primal against the barren landscape and the early 20th century "small town naivete" context of the film.

This will not be a long critique, it seems much ink has already been spilled about a film most people won't have the chance to see for at least a few more weeks. Also, I myself really wanted to see it again before I got too deep with a review, but I just couldn't wait any longer to write about it. It is a purely riveting picture and the always great Daniel Day-Lewis, as patiently dedicated oilman Daniel Plainview, is excellent beyond words. As the film unfolds, we have a front row seat for the events that occur to more and more disillusion and alienate an already detached man from the world, hacking away at what little faith he has left in humanity. The picture is almost a vehicle for Day-Lewis' grinding depiction of a man's slow descent into a self-imposed, isolated madness. Paul Dano, as the savvy evangelist Eli Sunday, admirably holds his own against the world's greatest working actor. The pitting of the fierce business man vs. the zealous religious man may seem obvious on the surface, but nevertheless, the dialogue and the actors make it deliciously primal against the barren landscape and the early 20th century "small town naivete" context of the film.

Radiohead's Jonny Greenwood lends a score that is reminiscent of the darkly classical pieces used by Kubrick in 2001 and Ennio Morricone's functional score from Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West. In that film, Morricone famously made music with the sounds of various natural elements in the film's wild west location: creaky doors; dripping water; swirling winds; lumbering trains; buzzing flies; antique  machinery; etc. Along with his dissonant strings playing the strains of hell (a prominent place for both the screeching preacher and the man who digs up the below), Greenwood echoes the unfeeling, dusty machinery of the desert and it's sonic similarity to the mechanical beating hearts of our main characters.

machinery; etc. Along with his dissonant strings playing the strains of hell (a prominent place for both the screeching preacher and the man who digs up the below), Greenwood echoes the unfeeling, dusty machinery of the desert and it's sonic similarity to the mechanical beating hearts of our main characters.

As for the hotly debated and prophetic ending, all I can say is that those people who were angry over The Sopranos' black-out, with its lack of confrontation and traditional climax, finally got their wish, their ultimate showdown. Now quit your bitching. It was orgasmic and insane and also the only logical conclusion: an epic blast after a long, slow boil; a final act of madness from a finally mad character. For further analysis, I cede to Richard Schickel's excellent summation for Time: "It is the genius (and I use that word advisedly) of Daniel Day-Lewis's performance to slowly, patiently, show the madness replacing his former rationalism, to prepare us for the film's astonishing ending, an ending one dare not reveal, but that contains what I — resistant as I am to superlatives — consider to be the most explosive and unforgettable 10 or 15 minutes of screen acting I have ever witnessed."

But enough about all that, you can check the links at the bottom for much more extensive reviews of the film than mine. What usually concerns me most with the films I watch is what they are trying to say about our species and about human nature. Without making any effort of its own to label characters "good" or "bad", There Will Be Blood addresses the demons in all of us. Whether or not we choose to chase and suppress these demons, and how much we are able to do so to make room for angels, seems to make the most difference. Add to this the sad fragility of sanity and it is easier to see what differentiates the best and worst of us. By the end of the film, both Plainview and Sunday are victims of all of these forces, of their collective experiences and lots in life, and most importantly, their ambitions.

I see Richard Nixon in Daniel Plainview. Like Nixon, Plainview is ruled by his insecurities as much as his ambitions, but he is not an inherently evil man, just a misanthrope; like the modest Nixon, he is not greedy for money in any traditional sense, only for power and the protected independence and freedom continued success can buy him; like Nixon, he is ruled in toto by insecure desires for acceptance, even from the masses, all the while viewing them as naive nincompoops; and like Nixon, Plainview is a "family man" who is capable of being fiercely loyal to his loved ones and colleagues, provided they are of benefit to his rise. Or, as he puts it: "I can't keep doing this on my own, with these... people." Plainview, even amongst a crowd, is always alone. His breathy and constipated laugh after this line confirms how much faith he has lost in the human race and the contempt with which he views it. He's learned, it seems, to take no one seriously but himself and his accomplishments. We are challenged throughout the first two hours of the film to like Daniel Plainview because we are shown his humanity as much as his misanthropy. We are shown others who are just as conniving as he and far more corrupt, which aids to keep Plainview in proper context against the rest of the world. Many films will force you to feel a certain way about an "evil" character by overloading the emphasis on the negative or the positive, depending on the goal. There Will Be Blood recognizes the dichotomies of all men (even Hitler was married and had a faithful dog, Blondi) and allows us to make our own judgments on Plainview, the equally suspect Eli Sunday, and others in the film who rise or fall based on their ambition or ineptitude. It asks us to question ambition itself, not greed, which is a refreshingly different way of attacking the much-hashed subject of big business, captains of industry, capitalism, and the American Dream.

We are challenged throughout the first two hours of the film to like Daniel Plainview because we are shown his humanity as much as his misanthropy. We are shown others who are just as conniving as he and far more corrupt, which aids to keep Plainview in proper context against the rest of the world. Many films will force you to feel a certain way about an "evil" character by overloading the emphasis on the negative or the positive, depending on the goal. There Will Be Blood recognizes the dichotomies of all men (even Hitler was married and had a faithful dog, Blondi) and allows us to make our own judgments on Plainview, the equally suspect Eli Sunday, and others in the film who rise or fall based on their ambition or ineptitude. It asks us to question ambition itself, not greed, which is a refreshingly different way of attacking the much-hashed subject of big business, captains of industry, capitalism, and the American Dream.

Ambition is necessary for any of us to succeed, of course, and as the greater devils of human nature have taught us, contained within certain unconscionable people it can sometimes lead to poverty, disease, holocaust, and war. Nevertheless, it is a survival skill. I do not think it is outside the lines to say that this film is a commentary on ineptitude and weakness as much as it is a commentary on ambition and strength, and that the weak must take some responsibility for their poor conditions. This goes for the successful man's failures to maintain control, humility or perspective as much as it goes for the foolish and apathetic who do not succeed.

We are taught to always be strong, to rise above adversity, to stand up no matter how many times we are knocked down, to find benefit from suffering. Or, as the paradoxical Richard Nixon said in his farewell address, "the greatness comes not when things go always good for you, but the greatness comes when you are really tested, when you take some knocks, some disappointments, when sadness comes, because only if you have been in the deepest valley can you ever know how magnificent it is to be at the highest mountain."

That goes for all the animals.

More excellent reviews:

Time Magazine

http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1698168,00.html

Daily Film Dose

http://dailyfilmdose.blogspot.com/2007/12/there-will-be-blood.html

N.Y. Times

http://movies.nytimes.com/2007/12/26/movies/26bloo.html

The House Next Door

(massive spoiler warning)

http://mattzollerseitz.blogspot.com/2007/12/drilling-for-art-there-will-be-blood.html

Quarter Life Comeback

http://quarterlifecomeback.blogspot.com/2007/12/tonight-faith-just-aint-enough-or-im.html

Lauren Wissot

http://www.psychopedia.com/outpost/

The Reeler

http://www.thereeler.com/reviews/there_will_be_blood.php

Thanks for the Use of the Hall

http://www.panix.com/~sallitt/blog/2008/01/i-am-not-convinced-that-p-t-anderson-is.html

Read more!

Posted by

Mark A. Fedeli

at

4:50 PM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, December 26, 2007

The Sopranos Finale: A Second Coming

No More Fuckin' Ziti

by M.A. Fedeli

So, after waiting for my girlfriend to finally finish The Sopranos episode 86, "Made In America" (otherwise known as The Last Sopranos Episode EVER!), I can now write about the show's farewell. It was, how do you say, almost perfect? Without being a snob, I never could understand people's reactions to the show in general, especially in response to the series finale. People I know who loved the show for all its familial angst and anti-climactic wonders, not just the mob violence, were somehow still shocked and/or "miffled" after the final finale. It hurts to say, but if you didn't get why the show ended like it did, worse yet, if you didn't see it coming in the least, then you probably didn't really understand the show and where it has been going since the end of season 1.

I'm not going to re-cap the last episode or the famous ending, if you haven't yet seen it or heard about it you live in a hole where I do not wish to also reside. Needless to say, it was a fitting touchdown to the overall trajectory the show had been heading in: the focus on themes of hopelessness and existentialism that began at the beginning with Livia's poison moaning and Tony's first woe-is-me therapy session. No one kept this lingering to the finish line as well as AJ, who, after his suicide attempt, reminds us that Livia once told him there's no point in life and you die in your own arms. In The Sopranos, characters commit sins, apologize, and then commit them again with alarmingly consistent repetition. With these types of notions being floated week after week (like AJ explaining that you'd have to be crazy to think the world is not), how could anyone wonder why it ended like it did? It was absolutely appropriate, intelligent, and honest, three traits that have always been harder to achieve than just entertaining. A monkey with cymbals is entertaining. David Chase, the creator of The Sopranos, must surely believe that there is no real closure or satisfaction in life. The show has always been most effective as a work of art for those who closely shared his darker world views. AJ's thoughts, his shock at the horrors of the world, while naive and said with little eloquence, are the truth, and he submits to them fully. Tony, while sharing many of the same dark thoughts, is the lie. Frequently two-faced, he uses these dark forces to his advantage, manipulating those around him, many times even unknowingly, and dragging everyone down to pull his way up. How ironic is it then that in one of his most touching, real, and sensitive moments as a father, he lifts AJ up out of the swimming pool, begging AJ not to fight him. It's moments like this that make us love him, his sympathy for the innocent and helpless. Sympathies that are fleeting and extend mostly to animals because they don't really annoy him or get in his way, as evidenced by the quick return to contempt for his son in the therapy sessions shortly after the suicide attempt.

David Chase, the creator of The Sopranos, must surely believe that there is no real closure or satisfaction in life. The show has always been most effective as a work of art for those who closely shared his darker world views. AJ's thoughts, his shock at the horrors of the world, while naive and said with little eloquence, are the truth, and he submits to them fully. Tony, while sharing many of the same dark thoughts, is the lie. Frequently two-faced, he uses these dark forces to his advantage, manipulating those around him, many times even unknowingly, and dragging everyone down to pull his way up. How ironic is it then that in one of his most touching, real, and sensitive moments as a father, he lifts AJ up out of the swimming pool, begging AJ not to fight him. It's moments like this that make us love him, his sympathy for the innocent and helpless. Sympathies that are fleeting and extend mostly to animals because they don't really annoy him or get in his way, as evidenced by the quick return to contempt for his son in the therapy sessions shortly after the suicide attempt.

Everyday, tons of awful things in this world happen with what seems to be no reason, no moral, no sense, no validation. Tony Soprano gave us a glimpse of one person who is responsible for many of those things, and we loved him (because of it or in spite of it?). I would guess that Chase was delighted with our collective hypocrisy, which the ending played on as much as it played on our expectations. The circle turns and turns, "the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity." To his friends and his family, Tony was oftentimes that rough beast that slouches toward Bethlehem to be born. Yet we rooted, in record numbers, for this man to succeed, to accomplish, to win. What does this say about us as a society, as a species? Despite the cliche, life is definitely a journey, not a destination. It's the Myth of Sisyphus. Same goes for The Sopranos. This show has been a great journey for the better part of a decade, shame on those who put extra stock into the unrealistic notion of "how it all ends". It kept your heart pounding up until the last second and far beyond it, is that not enough? For the violence and action fans it killed off 3 major characters and handfuls of regulars in the last 4 episodes, seriously and violently injuring a few more. It also gave us the tragic end of Christopher, a vicious curb stomping, Phil Leotardo's squashed head, W.B. Yeats, and AJ's brilliantly orchestrated and heartbreaking suicide scene. Not to mention the continued brilliance of the writers, Edie Falco, and James Gandolfini with all things related to the revolving dynamics of Tony vs. Carmella.

Despite the cliche, life is definitely a journey, not a destination. It's the Myth of Sisyphus. Same goes for The Sopranos. This show has been a great journey for the better part of a decade, shame on those who put extra stock into the unrealistic notion of "how it all ends". It kept your heart pounding up until the last second and far beyond it, is that not enough? For the violence and action fans it killed off 3 major characters and handfuls of regulars in the last 4 episodes, seriously and violently injuring a few more. It also gave us the tragic end of Christopher, a vicious curb stomping, Phil Leotardo's squashed head, W.B. Yeats, and AJ's brilliantly orchestrated and heartbreaking suicide scene. Not to mention the continued brilliance of the writers, Edie Falco, and James Gandolfini with all things related to the revolving dynamics of Tony vs. Carmella.

In the very, very end we were treated to one of the most well-crafted scenes in the show's, if not television's, history, managing to present both subtly and effectively at least three separate themes:

1) It used the audience's knowledge that there were only a few minutes left of the show, and played hard on it, allowing us to feel Tony's paranoia of being murdered at any moment. Time was running out on us, that clock trickling past 10pm EST was a dire reminder. When the screen goes black, it was us who was murdered. Seeing as everyone expects something substantial in a final scene, can you do any better than that? Just because there wasn't a titanic melodramatic on-screen resolution in the last 5 minutes, does that ruin the fact that you were absolutely riveted just the same, or invalidate scenes that came before? That a TV show made you feel that engaged and alive is a gift. Any number of possible endings floated prior to the finale (Tony getting whacked, Carm or the kids getting hurt, Tony arrested/flipping, etc.) now seem silly in hindsight. 2) It was the artful whacking ending, repeating again the idea that you don't even hear it when it happens. This was referenced this season first by Bobby in the boat, then echoed by Silvio with the Gerry Torciano whacking, and finally in Tony's safe-house, last-night-on-earth flashback. Add to this the already present tension, the ringing bell, Meadow's erratic parking, and the diner characters who clearly are all meant to represent possible or past threats, and you have a wonderfully thick dramatic and psychological stew (not to mention the nod to The Godfather and the final black thought that maybe, just maybe, Tony's brains were bada-bing, blown all over Carm's nice, zip-up sweater). This interpretation was obviously intended and heavily alluded to, but in the end, it's delightfully uncertain because nothing ever exists outside of what's in the frame.

2) It was the artful whacking ending, repeating again the idea that you don't even hear it when it happens. This was referenced this season first by Bobby in the boat, then echoed by Silvio with the Gerry Torciano whacking, and finally in Tony's safe-house, last-night-on-earth flashback. Add to this the already present tension, the ringing bell, Meadow's erratic parking, and the diner characters who clearly are all meant to represent possible or past threats, and you have a wonderfully thick dramatic and psychological stew (not to mention the nod to The Godfather and the final black thought that maybe, just maybe, Tony's brains were bada-bing, blown all over Carm's nice, zip-up sweater). This interpretation was obviously intended and heavily alluded to, but in the end, it's delightfully uncertain because nothing ever exists outside of what's in the frame.

3) It was the life goes on and on and on and on ending, wholly validating the originally curious choice of (coincidentally named) Journey's "Don't Stop Believin'" as the series' last song. This show, among other things, was about Tony and how his selfishness and insecurities could seriously affect everyone he ever got close to, and how he dealt with the fallout. But the show judged everyone equally. It called to task both of his "families", who were all far less than perfect, and who were hypocrites and liars themselves, right up until the end. AJ, Meadow, Carm, Janice, Paulie, Christopher, Melfi; no one was ever excused from being human. And so, the larger ending, the families, both of them, despite the years of threats and abuse, are still there, still repeating mistakes and living the same tortured lives they started at birth. And Tony, despite all the attempts (real or not) to better himself, is still there, still breathing heavy, still under constant threat. And the circle turns and turns and turns.

And that's the point. The build-up and the suspense are "the happening", they are the big finale. The journey is the event. When "Don't Stop Believin'" begins at around the show's hour mark, you think that the episode (and series) is going to end with a happy, upbeat song and a happy, upbeat family-gathering montage moment, as they have sometime done in the past. But this was the end of the show for all-time, and it just felt different. Action was rising, not falling. Drama was still being conducted. Most past episodes' final songs always played for a few seconds, but no more than a minute or so really, before the action noticeably winded down and the episode faded out to the credits. But as "Don't Stop Believin'" didn't stop and kept on going for 3 minutes, 4 minutes, 5 minutes, the tension was incredible. Absolutely white-knuckled. This had never been done on the show before; for anyone paying attention all these years, it was excruciating. Something HAD to happen; the longer the song played the bigger this "happening" was to be. And then, in a brilliant instant, in a big, big, way, it HAPPENED. It ended, with both a bang and whimper.

For years I've heard people complain viciously about the show yet never miss a minute of it. Makes you wonder what they thought about shows they didn't watch. Hyper-judgment seems to be the curse of the 86+ hour feature film for television that The Sopranos was. Keeping things interesting and revelatory, and keeping the standards up that high for that long borders on impossible. Especially in the face of our cynical, destroy-your-heroes world. The genius of the show, however, was the fact that it kept you glued, and no more so than in those final minutes. What more can you ask? If it were so easy to do and so common we'd love every TV show and movie and character out there; we'd be this collectively unnerved by their endings.

What more can you ask? If it were so easy to do and so common we'd love every TV show and movie and character out there; we'd be this collectively unnerved by their endings.

God bless David Chase and his balls for staying true to themselves and not being afraid to give us these entertaining doses of tough love. The overall final voyage of the show was philosophical and reflective, with characters constantly relishing and remembering the past (like they've always done). The more things changed, the more they stayed the same. The last chapters of The Sopranos were cold, sometimes anti-climactic, and may have even seemed alienating and confounding. But so what? That's life. Just ask Livia. With every other show not doing this, we should be happy such a great show did. We were not cheated in the least, we were given something more artistic, thoughtful, and lasting than all the blood spatter and screams in the world. Chase has said that he was not trying to be cute with the ending, that everything he was trying to say is in the scene. Problem is, it was exactly what the audience didn't want to hear: "the show is OVER." Let's be honest, the lack of a bloodbath is not what angered people, having to think more than just observe with interest is what did it. Having to reconcile with the disappointment of the show ceasing to exist is what was frustrating even to people who loved the sudden and unsympathetic black-out, like myself.

But don't take it from me, just read these David Chase quotes:

"This is what Hollywood has done to America. Do you have to have closure on every little thing? Isn't there any mystery in the world? It's a murky world out there. It's a murky life these guys lead. And by the way, I do know where the Russian is. But I'll never say because so many people got so pissy about it."

And, "We don't have contempt for the audience. In fact, I think The Sopranos is the only show that actually gave the audience credit for having some intelligence and attention span. We always operated as though people don't need to be spoon-fed every single thing--that their instincts and feelings and humanity will tell them what's going on."

In a Season Two episode, AJ mentions an existentialist quote which says that life is a choice between boredom and suffering. These characters have chosen suffering. And so it continues, in their lives and in ours...

Read more!

Posted by

Mark A. Fedeli

at

11:03 AM

4

comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, December 24, 2007

Killing You Where You Sleep

I Am Legend and the Spectacle of Familiarity

by M.A. Fedeli

My mother and I went to the IMAX theater in the Tropicana Hotel & Casino in Atlantic City to see I Am Legend. She really wanted to see a feature film on IMAX and I really wanted to see Big Willie be as big as possible. After about 5 minutes of establishing shots showing the vacant island of Manhattan and all of its landmarks, my mother whispered (quite loudly) "where does this film take place?" I saw a few heads around me roll and giggle. Nevertheless, the generation (and location) gap was apparent. I am inundated daily by promotion for this film and even walked through Washington Square while they were preparing a scene; all she knew was Will Smith and IMAX.  This contrast went along with recent thoughts I've had on how blowing up well-known landmarks has single-handedly saved the action-adventure, more specifically, disaster epic. In my parent's day, The Towering Inferno could be any old building in any old city. In my day, it had better be the Sears Tower or the Empire State for it to mean anything to the audience.

This contrast went along with recent thoughts I've had on how blowing up well-known landmarks has single-handedly saved the action-adventure, more specifically, disaster epic. In my parent's day, The Towering Inferno could be any old building in any old city. In my day, it had better be the Sears Tower or the Empire State for it to mean anything to the audience.

The film was decent for the first two acts, and there is nothing in the plot you couldn't guess from watching a trailer or two. It was a treat to see the city as barren wasteland. Bucking the latest trends, its running time wasn't long at all, probably too short, in fact. Mr. Smith's character's name is Robert Neville, a scientist and the last man standing on Manhattan Island. I could have easily done with another 15 minutes worth of scenes showing his descent into a lonely, paranoid madness (something that is portrayed inconsistently and not alltogether very believably). To take an even darker tone with the character's mental state would have ensured the Fresh Prince some major Oscar consideration, if he does not have it already. Overall, I had a great time, aside from some early hand-held shaky cam work that brought me to the threshold of nausea (see, when you're watching an IMAX film and can't focus your eye on something because everything in the frame is constantly moving, well, vomit is induced). One small detail I loved was in Robert Neville's Washington Square apartment, where he had great works of art from NYC musuems hanging about, including the MoMA's Starry Night, which was prominently placed above his fire place; a nice touch.

About two-thirds of the way through the film, though, just as our hero is seemingly about to meet his tragic end, all rationale and reason to care about the plot is lost. I know this film is based on a novel, but that's the writer's problem, not mine. A completely unbelievable and ridiculously contrived measure is taken to save his life and move forward the third and final act. Alas, I still enjoyed myself despite the absurdity and commented to moms, "it really is amazing what crap you'll let slide for the pleasure of spectacle and incredible special effects." So, as someone who quite detests CGI and most special effects, how can I say that? Because seeing my city in such a dramatic and unreal condition is the ultimate roller coaster ride. It is experiencing the thrill without the risk or danger. All it took to make me happy was seeing on that big screen the Union Square subway stop I frequently use, or the sign for Fanelli's Cafe in SoHo where I recently ate. Seeing your home in a movie has the same feeling as seeing a famous person on the street (except for my father, who apparently bumped hard into Jerry Seinfeld crossing a street and then told my mom he thought "that guy looked familiar.")

So, as someone who quite detests CGI and most special effects, how can I say that? Because seeing my city in such a dramatic and unreal condition is the ultimate roller coaster ride. It is experiencing the thrill without the risk or danger. All it took to make me happy was seeing on that big screen the Union Square subway stop I frequently use, or the sign for Fanelli's Cafe in SoHo where I recently ate. Seeing your home in a movie has the same feeling as seeing a famous person on the street (except for my father, who apparently bumped hard into Jerry Seinfeld crossing a street and then told my mom he thought "that guy looked familiar.")

The only thing we love more than seeing our home is seeing it blown to fucking smithereens (which is actually a real word). We can thank Will Smith again for that, with Independence Day. ID4 started the landmark-smashing craze that has been featured prominently in almost every respectable disaster epic since. New York City has bared the brunt of this destruction (but hey, that's because a destroyed NYC is devastating and regrettable, as opposed to a destroyed LA, which we all secretly hope for everyday anyway). The fascination with exploding White Houses and pummeled Empire States is the same exact emotion and attraction that had us watching the twin towers collapse over and over again. To this day, when the World Trade Center towers are shown falling on our TVs, who can ever turn away or change the channel? No disrespect intended, but viscerally, it is like a scene in the ultimate disaster film.

Will Smith is Hollywood's new leading man, taking over for middle-aged white men named Tom.  That is a very good thing. He also has a gift for inducing tearful empathy in the audience, as he did to me in certain flashback scenes in I Am Legend (he also had me bawling at the end of The Pursuit of Happyness). The bar for disaster films has been raised, and that's a very good thing too. Now, if only the producers would pay the writers as much as they pay the special effects guys, maybe we could get some plots that can hold up beyond the spectacle.

That is a very good thing. He also has a gift for inducing tearful empathy in the audience, as he did to me in certain flashback scenes in I Am Legend (he also had me bawling at the end of The Pursuit of Happyness). The bar for disaster films has been raised, and that's a very good thing too. Now, if only the producers would pay the writers as much as they pay the special effects guys, maybe we could get some plots that can hold up beyond the spectacle.

Posted by

Mark A. Fedeli

at

12:53 PM

5

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, December 20, 2007

The Doors: Pretty Good, Pretty Neat

Rethinking the Rock Biopic

by M.A. Fedeli

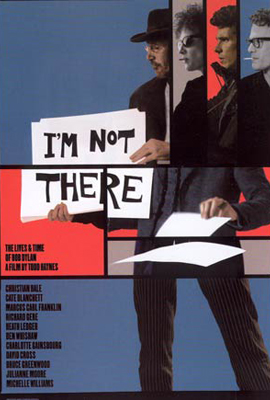

The debate over what makes a good rock biopic is a raging one. This can mostly be attributed to the frequent ineptitude of the genre. It is a difficult subject to capture, as I discussed in detail in my review of Todd Hayne's I'm Not There. Despite being a fascinating rethinking of the genre, one well known yet oft overlooked biopic is Oliver Stone's The Doors. This film is essentially the story of Jim Morrison, and to be fair, it is far from perfect, exhibiting some of the usual biopic faults. This can largely be attributed to the inherent bouncing around of rock biopics and the well-known ground they must almost contractually agree to cover in between standard character development. Many times they must forgo traditional narratives in order to include enough reenactments of the musician's most famous events and mythological rock n' roll stories that the audience yearns to see. The Doors probably requires the attention span of an above average Doors fan to sustain and the script labors a bit too much on the negatives of Morrison (his excesses, indulgences, and unsympathetic treatment of others). It tends to lean heavily on the legends and the infamous lore of the man, not having a balancing amount of the sympathetic dissection Stone would display in his operatic treatment of Richard Nixon. An excuse could be made that Stone wanted to challenge the audience to like this hero of theirs, asking them, "Would you really want to hang out with this son of a bitch?" Showing Morrison as the animal he could sometimes be was indeed a way to to show the dark underside of 60's rock super-stardom and hedonism.

The Doors probably requires the attention span of an above average Doors fan to sustain and the script labors a bit too much on the negatives of Morrison (his excesses, indulgences, and unsympathetic treatment of others). It tends to lean heavily on the legends and the infamous lore of the man, not having a balancing amount of the sympathetic dissection Stone would display in his operatic treatment of Richard Nixon. An excuse could be made that Stone wanted to challenge the audience to like this hero of theirs, asking them, "Would you really want to hang out with this son of a bitch?" Showing Morrison as the animal he could sometimes be was indeed a way to to show the dark underside of 60's rock super-stardom and hedonism.

I see it though, as a flaw in the performance of Val Kilmer, who has been lauded by fans for his uncanny portrayal of Morrison and his vocal stylings. However, he does not do what Anthony Hopkins did so wonderfully in Nixon, focusing more on the inner turmoil of the man and capturing his essence, rather than delivering an inspired impersonation. Nixon makes you stop searching in the film for the real man and immerses you in the film's own reality. Kilmer does an excellent and believable job, to be sure, but the performance lacks the heft to be transcendent. The negatives of The Doors pretty much end there.